Dr. Jennifer Peeples has examined the discourse and images of environmental protest and corporate response, and, most recently, the visual construction of toxicity. She recently spoke to Annenberg PhD candidate and Center Steering Committee Member Hanna E. Morris about the inspiration behind her work, including her forthcoming book Toxic Imaginary.

Your scholarship bridges many disciplinary divides—environmental communication, visual rhetoric and social justice (to name a few). Do particular issues or questions continually motivate your scholarship? Or have you found that the questions you ask have changed over the course of your career?

I have two lines of environmental rhetoric research, which are only tangentially connected. The first investigates the rhetorical challenges to mainstream environmentalism from the left and the right. From the right, I examine political and industry campaigns intended to frame environmentalism as a threat to neoliberalism. One of my first research projects explored the discourses of the Wise Use Movement, a group organized to challenge environmental regulations. From the left, I have researched environmental justice and anti-toxins actions and advocates, who have argued that mainstream environmentalism excludes urban concerns, working-class individuals and communities of color. While recognizing the importance of traditional environmental organizations and policy, those aspects of environmentalism have not sustained my academic interest. The rhetoric of the diverse groups that have questioned environmental assumptions, science and practices in the US has always held much greater allure for me, even when–as is the case of the attacks from the right–I vehemently disagree.

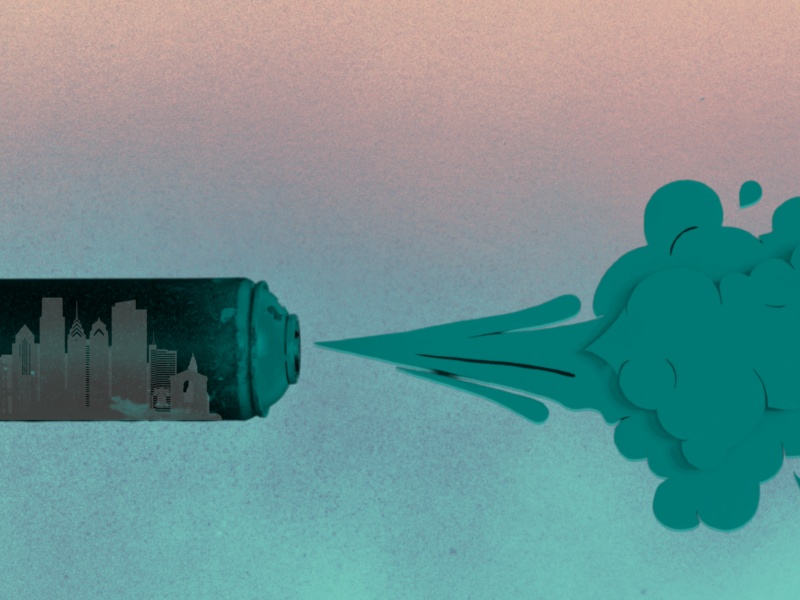

The second line of research partially comes out of my work on anti-toxins discourses and partially from living in Vietnam when the Vietnamese government was suing the US over its decision to dump dioxin-laden Agent Orange over the jungles and cropland during the Vietnam War. The question I explore in this work is, “how do we see toxins?” As toxins are either banal (endocrine disrupters in one’s shampoo) or invisible (radiation), toxins must be symbolically constructed for people to recognize their noxious effects. In what ways is this done and what are the potential outcomes of particular visual constructs?

Your past and current work often centers the visual communication of environmental issues—why are visuals so important?

There are so many ways to answer this question! With our screens held tightly in our hands and the undeniable cultural and global impact of TikTok, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, Facebook (and other platforms I’m too old to know about), means that not having something to show often means not having something to say. Amongst a host of functions, the repetition of images’ content and design (re)create culture and social norms, such as what “nature” looks like. Images iconize certain events or locations (Half Dome in Yosemite), provide evidence of acts that are normally unseen, ignored or dismissed (dumping waste; hunting whales), and can appeal to vast audiences who share neither culture nor language. For my work, I began as most rhetoricians do, primarily examining the written and spoken word. At some point early in my career, I realized I was critiquing environmental discourses with one theoretical arm tied behind my back. From the Sierra Club calendars to people dressed as polar bears enacting a die-in to protest climate change, not examining images meant I was missing some of the most vibrant and powerful forms of environmental rhetoric.

Some scholars are noting how fossil fuel companies and mining industries are moving from an outright denial of climate science to more subtle forms of obstructionism. Are industry narratives changing? If so, how? Why do you think rhetorical strategies are shifting (or not)?

Industry discourses are changing significantly. My co-authors and I examined this phenomenon in our book Under Pressure: Coal Industry Rhetoric and Neoliberalism (2016). As the title hints, we chose to examine the rhetorical strategies of the coal industry because it is the lowest hanging fruit of the fossil fuels. It is almost singularly used to generate electricity, as opposed to oil, which is used in transportation and innumerable consumer goods. Coal is the dirtiest fossil fuel and, with improved extraction due to fracking, natural gas has become cheaper to produce and is cleaner to burn than coal. Under attack on all fronts, the coal industry has engaged in a variety of public campaigns that have become the playbook for other controversial fossil fuels, such as the oil sands in Canada. While there has been a lull in the public campaigning for fossil fuels during the Trump administration (the industries felt in good hands), we anticipate seeing these strategies used by other fossil fuel industries as they also begin to feel increased pressure from government action and the expansion of renewable energy resources, such as wind and solar.

In brief, some of the strategies we found included the use of industrial apocalyptic narratives, especially around the fallacious “devastation” of the economy from environmental action. The narrative frequently advocates a doubling down on fossil fuels to avoid the oncoming economic disaster. The technological shell game is played when industry touts certain technologies for their ability to mitigate environmental impacts (such as capturing and storing carbon to lessen climate change), when the technologies are unproven, unscalable and/or bolstered by evidence of the technology’s effectiveness based on a different pollutant (in the case of coal industry, sulfur not carbon). The shell game works to derail federal regulation (“our technologies have solved the environmental problem you are trying to mitigate”) and at the same time sets up industry for millions of dollars of federal funds for technological research and development. As we were writing the book, a number of grassroots coal groups—often depicted with American flags, trucks and a “hometown” rural feel–were shown to be fronts for the coal industry. We refer to the coordinated messaging between these groups as corporate ventriloquism. This is not a new strategy, but is still important to examine, as social media amplify these voices. As is seen in response to environmental protest, industry spokespeople and coal-supporting politicians frequently refer to protesters as hypocrites if they drive to the protest in a car, live in a home with electricity or use plastic. The hypocrite’s trap also includes a healthy dose of disdain, as the industry supporters question the naiveté or common sense of anyone who believes it is possible to reduce dependence on fossil fuel when clearly everyone is reliant upon it. Finally, as the industry has begun to recognize that western countries are moving away from coal, it has attempted to make the moral argument that fossil fuels are necessary to move people out of poverty, with coal being the key to ending energy scarcity in the world. This neo-colonialist argument yet again asserts that the industries know what is best for poorer nations. The fact that these are the exact people who will be most hurt by climate change, and therefore may not appreciate having coal target their nation, does not appear to be part of industry’s decision making.

While less often issuing an outright denial of climate change, all of these rhetorical strategies are intended to bolster the belief that continued fossil fuels use is patriotic, moral, common sense and (most importantly) inevitable for the future.

I know you are almost done with a new book manuscript—congratulations! I’m very excited to read it. Could you tell us a little bit more about your forthcoming book?

Thank you! There is still some writing left to be done, but the end is in sight. In Toxic Imaginary, I explore the question I asked above: “how do we see toxins?” Toxins are frequently invisible. We cannot see them without the aid of technology (such as radiation in the air or arsenic in the water), the polluted site is hidden from view, or the toxins are so normalized that we do not perceive the potential for contamination and disease in the products we keep in our homes. The toxic imaginary, as I define it, is the collective stories, images, symbols and rituals that individuals and societies use to navigate the uncertainty of living in a toxic environment. With ego acting over common sense, in this project I set out to write a chapter on every way toxins are imaged. I spent innumerable days Google searching terms like toxins, contaminant, pollution, health hazards, environmental catastrophes, etc. I would not suggest this task for anyone trying to lessen their toxic paranoia or improve their general outlook on life.

The first substantive chapter of the book discusses hazard and warning symbols, such as those seen in hospitals (the radiation sign). I examine the rhetorical impact of design (color and shape, abstraction) in conjunction with the aim of providing warning. A significant portion of the chapter examines how these symbols function for intended and– more important–unintended audiences. For this project, I more commonly focused on photographs. In one chapter, I use the spraying of the dioxin-laden toxin Agent Orange in Vietnam as the case study to examine how a series of images can construct a definitive toxic narrative that differs from its often ambiguous discursive counterpart. In another, I examine the tensions inherent in visually constructing toxic landscapes as sublime (beauty and ugliness; known and unknown), as is the case in the photographs of Edward Burtynsky and other new topographic photographers. While focusing on the sublime, I kept setting to the side images of tailings ponds, garbage mountains, spewing pipes, plumes of black smoke coming from burning tires and other more repellant images. This categorizing led me to examine the images of the toxic grotesque. In addition to the hazardous warning signs, images of smokestacks and dripping drainpipes are the most common way toxins are constructed visually. In this chapter I explore why that representation matters. Researching the toxic grotesque, I was also reading about the use of bodies during Carnival, which led me to focus a subsequent chapter on how toxin-altered bodies are used in protest to show the presence and uncontrollability of toxins in the environment.

Taking a break from the more difficult subject matter (who really thought this was a good idea?), the next section was unintentionally initiated by my teenage son. Toxins are ubiquitous in comic books. The Red Hood jumps into a vat of toxic waste and becomes the villainous Joker. Baby turtles are hit with a canister of toxic goo and grow to be The Mutant Ninja Turtles. And the number of heroes and villains transformed through contact with radiation is extensive. The repetition in the presentation of technologies, science, government, industry and the privileging of urban environments found within these toxic transformation narratives brings into relief problematic eco-modernist ideologies, assumptions and solutions, which are dismissible for a comic book but troubling for environmental action. Finally, using the case study of the lead poisoning of Paris from the Notre Dame fire, I examine toxins as vibrant matter and advocate understanding the relationship between symbols and toxic matter as a collaboration, or more specifically, a co-laboring of sorts, with more or less catastrophic outcomes depending on the enactment of that process.

Thank you for your interest in my work and for giving me the opportunity to reflect on what continues to be a fascinating, yet challenging, subject area to study.

Dr. Jennifer Peeples is a Professor of Communication Studies at Utah State University. Her work uses environmental and visual rhetoric to examine discourses of energy transition and the construction of toxicity. In addition to journal articles and book chapters, she is the co-author/co-editor of three books, including Under Pressure: Coal Industry Rhetoric and Neoliberalism (2016), and Voice and Environmental Communication (2014). Dr. Peeples will be delivering the Keynote Address for the virtual International Communication Association Pre-Conference “Visions of Change: Communication for Social and Environmental Justice” on May 27, 2021 at 1PM EST. The keynote will be open to the public. Please register in advance here.

Hanna E. Morris is a PhD candidate and Center for Media at Risk Steering Committee Member at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania where she is currently finishing her dissertation entitled “Apocalyptic Authoritarianism in the United States: Power, Media, and Climate Crisis.” Hanna’s research and writing have been published in various academic journals and popular media outlets including Environmental Communication, Media Theory, Reading The Pictures, and Earth Island Journal. She is the co-editor of the forthcoming book entitled Climate Change and Journalism: Negotiating Rifts of Time.